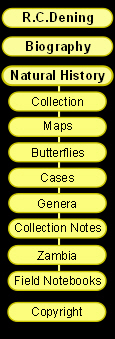

The R.C. Dening Collection |

|

Introduction to Zambian Butterflies

by R.C. Dening F.R.E.S.

Biogeography

|

INTRODUCTION |

| Zambia is primarily a savanna country with elements of rainforest, afro-alpine

and desert biomes around its borders. In Carcasson's eco-geographic divisions of the

Afrotropical Region, Zambia in general, falls within the Southern Division of the

Sub-region of Open Formations, and in particular within the Zambezi Zone. However, the borders of the country abut on other zones, considerably increasing its butterfly fauna; many further species may well be discovered with year-round collecting in these border areas. Thus at the Victoria Falls, where the Satyrid Mashuna mashuna occurs on the Zimbabwe side, no confirmed Zambian records are yet available.Further to the southwest, where only limited recording has occurred, the border lies close to the Kalahari Zone, altering the species balance in favour of desert and dry bush conditions. The occurrence seems not unlikely of such species as the pierid Colotis agoye and Acraea stenobea, the latter mentioned in Carcasson for Zambia, but of which the present author knows no specimens.In the east, proximity to the Eastern Zone introduces numerous species such as Charaxes chinteche, Euryphura achlys, and many lycaenids. Here also there is contact with the Malawi-Nyasa Zone of Carcasson's Highland Forest Division, with the inclusion inter alia of Papilio jacksoni nyika and Cymothoe cottrelli. Moreover, within Zambia on the Nyika Plateau, there is a small area of Tropical Montane Grassland, where the fritillary Issoria smaragdifera and the Small Copper Lycaena phlaeas occur. Right across the northern border, in numerous places, elements of Carcasson's Lowland Forest Division (Sylvan Sub-Region) infiltrate from the Congo Zone. However, with altitudes of around 1,200 metres, these areas can only be considered lowland forest by contrast with Highland or Montane Forest.The great African Central Forest Block extends, in many areas unbroken, from the remaining West African forests through Cameroon and the Congo Republics on the northwest, Angola in the west, and right across the continent to Rwanda, Burundi, Uganda and Western Kenya in the east. Across this vast area, thousands of species range, often represented by subspecies in particular areas. Thus many areas in the north of Zambia have a surprising riverine rainforest fauna, in particular northwest Mwinilunga, the Copperbelt, northern Luapula, Lake Mweru and the Lake Tanganyika southern shores. The likelihood of undiscovered species in these areas remains high provided the habitats are conserved.

The Influence of Past Climatic Changes

|

RAINFOREST BIOMES |

| Over much of

geological time, the climate of Africa has alternated between periods of considerable

aridity, followed by periods of heavy rainfall. This process has continued until

relatively recent times (Adams et al., 1996, The Physical Geography of Africa). Lake basin levels indicate a wet period between BP (= Before Present) 27,000-21,000 years, when rainforest may have extended over much of northern Zambia. There was then a period of aridity during the last northern Ice Age, at its most extreme around the last Glacial Maximum (BP 18,000). This is believed to have caused mass extinctions over large areas of the continent, so that the rainforest survived mainly in isolated refugia. This severe aridity continued until about BP 12,500, when there was a slow return to humid conditions. Lake Cheshi in Mweru Marsh gives a good indication of the chronology, its lowest levels having occurred between BP 15,000-13,000, and its highest levels between BP 8,000-4,000. The latter largely coincides with the Holocene warm period, after which there was a rapid decline to present lake levels. It seems likely, therefore, that as recently as 4,000 years ago, there were substantial areas of rainforest in northern Zambia, which had been re-colonised by numerous butterfly species from more northerly refugia.

|

AFRO-ALPINE FOREST BIOMES |

| Similar extreme

fluctuations appear to have occurred in relation to temperature at higher altitudes, as

indicated by the levels of glaciation on East African mountains. These also reached a

maximum in the late Pleistocene, around the northern Glacial Maximum (circa BP 15,000).

Since this was a time of great aridity, the additional ice cover was more likely due to a

temperature decrease rather than to a higher rainfall. A temperature depression of 5șC would bring down the main montane forest biomes from 1,500 metres to 700 or even 500 metres. Calculations to date suggest that current montane forest levels have remained roughly the same for the last 10,000 years, but back at BP 12,000 they extended to 30% lower altitudes. This could explain the discontinuous distribution of many forest species, which occur today in the East African coastal regions. The Satyrid Aphysoneura pigmentaria, which within Zambia is found on the Nyika plateau and the Mafinga and Makutu Mountains in the northeast, has been shown by Kielland to occur only above 1,500 metres (with one East African exception), even though its foodplant (bamboo) extends below this altitude (Kielland, 1989). This has resulted in the isolation of eleven distinct populations, which Kielland has identified as subspecies; some separated by considerable distances (over 400 km in the case of ssp. vumba). If 12,000 years ago, the climate which now prevails at 1,500 metres, occurred at 1,000 metres, these population discontinuities become more readily explicable.

|

DESERT BIOMES |

| Relict dunes of

Kalahari sand extend northwards right up the western borders of Zambia, virtually to the

Zambezi/Lualaba watershed. The Cryptosepalum forests, known locally as mavunda,

extending from south of Mwinilunga station to Kabompo and Kaoma, grow on soils with a high

sand fraction; while the Mundwiji Plain, north of the Mwinilunga/Solwezi road, is too

sandy and shallow for the growth of any but dwarf woody plants. Several phases of dune activity have been recorded in the late Pleistocene, though satisfactory dating has yet proved elusive. It would not be surprising if they too coincided with the Northern Hemisphere Glacial Maximum and the contemporaneous arid period in Central Africa. In all these sandy areas butterfly re-colonisation, on the return of wetter conditions, would likely have owed as much to Southern African biomes as to the rainforest biomes expanding from the north.

|

TODAY'S SAVANNA BIOMES |

| The detailed

classification of biomes is based initially on vegetational characters since: (a) Vegetation is the entry point of energy into the ecosystem, through the fixation of carbon; (b) It is a reliable indicator of other environmental variables; (c) It is an indicator of dependent animal species. However, in many cases butterfly distributions are only loosely related to the vegetational classifications. Provided foodplants are available and the microclimates are satisfactory for the species, it may occur in most vegetation types. Larsen (1991) listed 33 species as having a Pan-African distribution, an additional 73 species as occurring in all African Open Formations, and a further 139 species as being characteristic of Zambesian Open Formations. However, many of these species are not found universally within these main categories, but are restricted to particular areas by microclimatic and other factors. Adams, M.E., writing on Savanna Environments in the Physical Geography of Africa (Adams et al., 1996), quotes the following definition of Savanna:"All tropical and subtropical ecosystems characterised by a continuous herbaceous cover of C4 grasses that show seasonality related to water, and in which woody species are significant, but do not form a closed canopy or a continuous cover." (Frost et al., 1986). Adams then describes six main types of savanna habitat: 1. Savanna Woodland. Tall trees over 8 metres and up to 20 metres high; deciduous and semi-deciduous; spaced at more than the diameter of the canopy; rainfall 600-1500mm per annum. This includes Brachystegia-Julbernardia (Miombo) woodland, Cryptosepalum forest on the northwest sandy soils, Baikiaea plurijuga woodlands on deep Kalahari sand, and Colophospermum mopane woodlands on river basin clay soils in the south. 2. Savanna Parkland Scattered deciduous trees over 8 metres tall, generally of Acacia, Piliostigma. Terminalia and Combretum species, growing in grassland; rainfall, 400-800mm per annum. 3. Savanna Grassland Tall, tropical grassland without trees or shade; includes wet and marshy places. 4. Low Tree and Shrub Savanna Widely spaced, low-growing trees and shrubs, often over 2 metres high, with low-growing perennial grasses and abundant annuals; rainfall, 350-400mm per annum. 5. Thicket. Unstratified tree and shrub communities, e.g. of Acacia, Commiphora and Mopane. 6. Intermediate Vegetation with a preponderance of, for instance, Burkea, Terminalia and Combretum species. Adrian Storrs, on the other hand, in his 'Know your Trees', divides the vegetation of Zambia as a whole into four main groups: Closed Forest, Open Forest or Woodland, Anthill Vegetation and Grassland (Storrs, 1979). His Closed Forest classification includes montane forest, swamp forest and riparian forest, which for butterfly ecology are not a true part of the savanna biome, and will be discussed separately. His other types of Closed Forest (Copperbelt Parinari forests, Northern Province Marquesia forests, western Cryptosepalum forests, and southern Baikiaea forests) coincide only in part with Adams' Savanna Woodland. While the canopy may often be closed, and the first three genera evergreen, it seems inappropriate to treat these areas, for butterfly ecology purposes, as Rain Forest rather than Savanna Woodland. Storrs' Lake Tanganyika Itigi thicket corresponds to Category 5 above. He classes other components of Adams' category 1 as Open Forest or Woodland, such as Miombo Woodland, Hill Miombo, Kalahari Woodland, Mopane Woodland and Lake Basin Chipya. His Munga or Savanna Woodland, and Kalahari Sand Chipya, would fall into Adams' category 2.

|

Continue to