|

Background |

|

My

childhood holidays were often punctuated by the screeching of brakes and the choking

swirling of our following dust cloud into the car, as we pulled to a halt on the side of a

dry, dusty, dirt road in Africa, en route to some exciting destination. My father (R.C. Dening), having

caught a glimpse of an unusual or unrecognised butterfly, sliding tantalisingly across the

windscreen in the slip stream of our passage, would then leap out of the car brandishing

his trusty, battered, black, butterfly net and disappear into the surrounding Acacia scrub

in hot pursuit. The rest of us would look at each other in dismay and resign ourselves to

at least half an hour’s wait in the car until my father returned, elated with success

or perhaps making plans to return and try again at some later date. |

| . |

| He was without doubt, one of that rare

breed of people whose passionate interest in natural history in general and in his case,

Lepidoptera in particular, consumes their whole life. His

interest in natural history was fostered as a young boy through collecting butterflies and

insects around his home and at school. Later on, after the Second World War, he took a

post in the colonial administration in Northern Rhodesia (which became Zambia after

independence in 1964). Finding himself immured in the depths of the bush for years at a

time with few or no recreational outlets, he once again turned to his boyhood passion. (My

mother, while largely an unwilling accomplice in all this, nevertheless always knew when

she had seen a ‘new’ butterfly and is credited with the discovery of at least

one new species!)

My father died some time ago, bequeathing me the considerable

responsibility of safely disposing of his extensive collection of butterflies, moths and

dragonflies, collected over a lifetime of work and travel in various far flung outposts of

the world.

|

|

The collection consisted of

75 cases of meticulously documented, named, preserved and pinned specimens. Many of them were collectively so beautiful that it took your breath away

when you opened the lid and the hitherto hidden, jewelled colours inside suddenly

reflected the light in all their glory. |

| In the process of successfully

relocating his collection to a new home (the Glasgow Museums Resource Centre in Scotland)

and producing a website to publicise the collection’s existence, I have been mulling

over the modern-day, thorny issue of collecting specimens.

I personally have no desire to collect the real thing as my father

did, preferring instead to observe and collect images with the aid of a digital camera*.

However, in my opinion, the benefits of collecting and preserving specimens in the pursuit

of scientific knowledge, far outweigh any possible negative impact resulting from the

removal of a few specimens from a population.

*Digital

images, although certainly useful, are no substitute for a preserved specimen as a

verifiable record. There are a number of reasons for this:

- Creation of a digital image often introduces unwanted

artefacts such as shadows and improper colour recording because of the angle of the shot

and the lighting or camera settings.

- It is often impossible to photograph relevant portions of the

anatomy of a live specimen to show the specific anatomical features used for

identification purposes. For example, determination to species level in many cases

requires that the genitalia of specimens be examined under a microscope. It is simply not

possible to record such features with a digital image of a live specimen.

- There are issues with the long-term storage of digital records

- who is to be responsible for this? Who will ensure that such records are transferred to

new storage media as technology moves on and digital data storage methods evolve?

A preserved specimen, provided it is properly looked after,

can last for hundreds of years providing a verifiable physical record of anatomical

features and genetic material. |

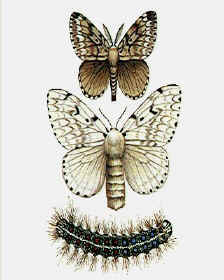

Our current knowledge and understanding of the

natural world and its mind-blowingly complex workings, is based head and shoulders upon

the body of the efforts of all the great naturalists and collectors of the past. Without

them, we might still be under the mistaken impression that caterpillars and butterflies

were entirely different animals and completely unrelated!

|

The Collectors |

| The history of collecting can be traced back over 300 years to the the late

17th Century. The earliest known natural history collections were beginning to be put

together at around the time when Galileo was getting into trouble with the Spanish

Inquisition, for championing Copernicus' idea that the Earth revolved around the Sun

rather than the other way round. One of the oldest insect

collections still in existence belonged to a gentleman named Leonard Plukenet, who lived

from 1642 - 1706. He was primarily a botanist and apparently an exceedingly competent one,

acting as personal botanist to Queen Mary II. His work was reportedly admired by Linnaeus,

who was a contemporary of his, as well as being accredited with being the father of modern

taxonomy (the naming and study of the relationships between organisms).

Plukenet's insect specimens were treated similarly to his extensive

collection of plant specimens; just pressed flat and then glued onto the pages of a

leather bound volume. His natural history collection was later acquired by Hans Sloane

(1660 - 1753) and now forms part of the Sloane Collection held by the Natural History

Museum in London. |

|

Natural

history collectors have come from all walks of life. They have ranged from duchesses, to

physicians, parsons and politicians.

Motives for collecting have varied from a basic impulse

to ‘stocktake’ the natural world, to the desire to possess beautiful things or

rare curiosities. From my perspective, the most important motive of all has been the quest

for understanding. |

| Many

collectors were serious scientists who laid the foundations for our current understanding

of genetics, variation and evolution. Some of them spent their entire lives pursuing

natural history knowledge through collecting, rearing and documenting specimens.

| (I remember as a child, sleeping unusually in

my sister's bedroom, which also doubled as my father's study. I spent much of the night

huddled under the bedclothes in abject fear because I interpreted the repeated scratchings

coming from behind the wire mesh screens on the open, ground-floor window, as signs that a

burglar was trying to gain entrance. With day

break, I discovered that the sound was actually emanating from the row of cardboard shoe

boxes on the window sill, containing a variety of hungry, munching (and scratching)

caterpillars being lovingly reared by my father. To say I felt incredibly foolish would

have been a major understatement!) |

|

|

Those collectors on a quest

for natural history knowledge are responsible for our understanding that insects have a

variety of life cycle stages. They worked out that eggs, caterpillars, pupae and

butterflies/moths (which bear no resemblance to each other and indeed are often found in

entirely different places) are actually stages in the life of a single individual. They also worked out the food plants favoured by different caterpillars and

connected together the disparate life cycle stages of many different species, so that the

caterpillars and young stages could reliably be assigned the same name as the adult stage. |

| . |

|

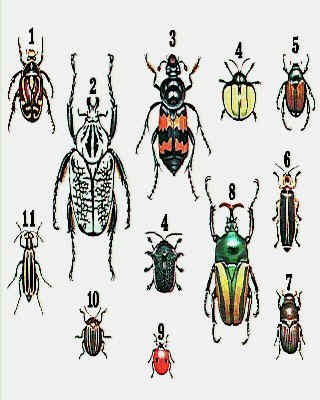

You might think that this

would be a relatively easy task, at least in Britain, where biodiversity (the variety of

life) is a fraction of that in some tropical hot spots. However, while there may be only

approximately 60 species of butterfly in Britain, there are over 2,400 moths, around 4,000

beetles and almost 7,000 flies! Connecting the life cycle

stages of all these together represents a truly Herculean task. In many places in the

world, this still remains to be done. |

| Much of our current knowledge of species, their habits, life cycles and

ecological requirements only exists because of the eagle-eyed observation and attention to

detail of these past collectors. It is because of their activities that we now understand

some of the subtleties of habitat requirement of different species and it is this which

enables us to manage to conserve them today. |

Museums and Collections |

These

days, collecting wildlife specimens of any sort is considerably non PC. Concerns over

extinction of species and conservation of natural resources have made it an absolute

public ‘No no’. However, there are some circumstances where collection of

specimens is a must. For example, new species/ subspecies or variants which are described

for posterity must always be backed up by preserved ‘Type’ specimens. These act

as a reference point for anyone else finding a similar species, to decide whether it is

the same or different.

This process goes some way towards preventing a species

being ‘discovered’ more than once and ending up with different names in

different places. If this happened too often, you would end up with taxonomic anarchy and

no-one knowing whether they were sharing information about the same or different species.

At this point, museums which maintain natural history collections come into the equation.

Their role is absolutely vital to ensure continuity and on-going maintenance of sometimes

fragile, incredibly important reference specimens which might otherwise be lost to time

and the depredations of insect and fungal pests. Apart from type specimens, the

collections which museums hold are in many cases legacies from enthusiastic collectors

such as my father. Museums and the specimen collections they display also play a very

important role in promoting public education and interest; - reading about or seeing a

picture of something is not nearly as exciting or instructive as seeing it in the flesh. |

Genetic Bar Coding |

| . |

|

The

collections held by museums and private collectors may now also have a pivotal role to

play in the development of new technologies such as the genetic bar coding of species.

DNA bar coding is one of the latest advances in gene

technology. By analysing a section of a gene contained in the mitochondria (tiny

organelles inside cells which are the power houses of the cell) researchers are redefining

many species relationships and in some cases finding that what has been thought to be one

species is actually a group of closely related species.

Many scientists around the world are currently working

to inventory the relevant fragments of DNA from various groups of plants and animals.

Museum collections offer them an unparalleled resource of named and documented specimens

for DNA retrieval and comparison.

(Image courtesy of Wikipedia. Click on the image to go to the source) |

| . |

This new gene technology

is considerably revising our understanding of relationships between species (although it

is by no means foolproof). It could conceivably result in portable, hand-held devices

which could immediately identify a species from a scan of its body, in much the same way

that bar-coded items are scanned at a supermarket. (Roll on the day! I have been calling

for bar coding of species, tongue in cheek, for years, never expecting such a thing to be

remotely possible.) |

|